In a nutshell

- 📚 Literacy is broader than reading; it includes numeracy, digital, and health literacy, building cognitive reserve that supports better decisions and longer lives.

- 🧭 Strong literacy reduces mortality risk by improving medication adherence, screening uptake, and navigation of NHS services—small competencies that compound over decades.

- 🗺️ Place matters: deindustrialised, coastal, and rural areas face intertwined health inequalities and literacy gaps, where opaque information design becomes a barrier to care.

- 🛠️ Practical fixes work now: use plain English, adopt teach‑back, redesign appointment letters, simplify labels, and make digital pathways low‑data and mobile‑friendly.

- 🎯 Investing in literacy is a cost‑effective public health intervention with spillovers into productivity, prevention, and social cohesion across the UK.

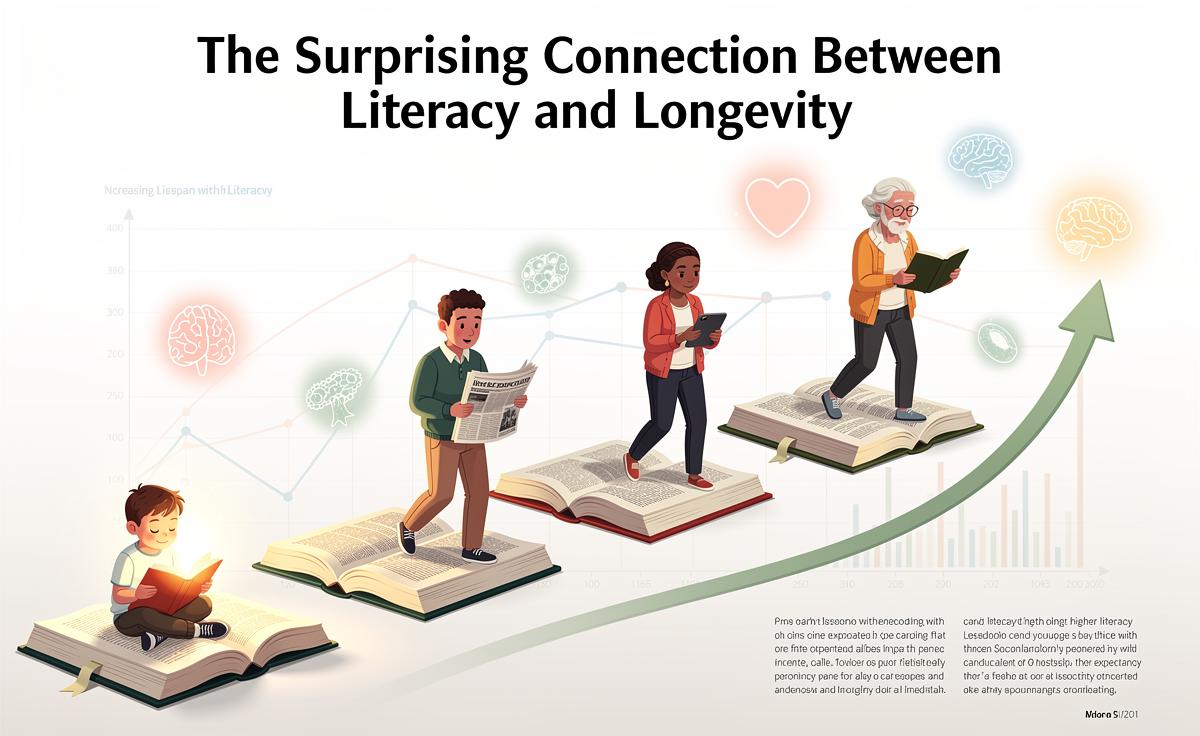

It sounds counterintuitive at first glance: how we read, calculate, and interpret information can shape how long we live. Yet across the UK and beyond, evidence keeps converging on the same idea. Literacy is a quiet determinant of health, linking the classroom to the clinic and the workplace to the ward. Think of it as a life-wide competence, not a school subject. It spills into how we navigate GP appointments, fill prescriptions, and weigh risks. Literacy is not just about books; it is a survival tool. When policy talks of “levelling up”, the most powerful lever might be the most overlooked one: the ability to understand and use information.

What Scientists Mean by Literacy and Why It Matters

When researchers talk about literacy, they rarely mean reading novels. They mean functional skills: reading, writing, numeracy, and the ability to apply information to decisions. Health services add another layer, calling it health literacy—the capacity to find, understand, and use health information. The difference matters in real life. A person might read well, yet struggle to decode a medicine label, an appointment letter, or a screening invitation. In the NHS era of online portals, “digital literacy” joins the list, shaping access to appointment booking and test results.

Scientists also consider the brain’s protective buffer, known as cognitive reserve. People who regularly read, learn, or tackle complex tasks often show delayed onset of cognitive decline. That reserve can influence employment, independence, and safety, all of which relate to longevity. In public health terms, literacy is a pathway variable—one of the channels through which education and income translate into health. Measured across communities, higher literacy tends to align with better prevention, quicker help‑seeking, and fewer avoidable complications.

Pathways From Reading Skills to Longer Lives

The mechanisms are strikingly practical. Better readers interpret dosage instructions accurately, decreasing medication errors. They parse risk, understanding why hypertension without symptoms still needs treatment. They navigate systems—knowing which service is urgent care, when to call 111, and how to challenge a confusing letter. This supports prevention and timely treatment. Economic pathways matter too. Literacy opens doors to safer jobs and steady income, easing chronic stress. Taken together, these threads tie literacy to lower rates of smoking, improved diet quality, and higher uptake of screening. Small competencies accumulate into long-term survival advantages.

Patterns seen across cohort studies and service audits often look like this:

| Measure | Lower Literacy | Higher Literacy |

|---|---|---|

| Understanding of medication labels | More errors, missed doses | Fewer errors, consistent use |

| Screening uptake (e.g., bowel, cervical) | Less likely to attend | More likely to attend |

| Smoking and risky drinking | Higher prevalence | Lower prevalence |

| Late presentation to services | More frequent | Less frequent |

Behind those lines sit daily realities: booking appointments on time, understanding red‑flag symptoms, and accessing support before a crisis. Mortality risk is the visible tip of that iceberg.

Inequality, Place, and the Literacy–Longevity Gap

Where you live in the UK can shape both your reading skills and your life chances. Deindustrialised towns, coastal communities, and rural areas facing poor transport and patchy broadband often endure intertwined challenges: lower wages, fewer training routes, and thinning public services. Health inequalities grow in these conditions. So does the literacy gap. When NHS information arrives in dense bureaucratic language, it compounds the problem. People who most need services find them least navigable. Information design becomes a gatekeeper to care.

There are also population groups who face additional barriers: recent migrants encountering unfamiliar systems and language hurdles; people with learning disabilities; those in prison education settings; older adults who missed out on schooling or now face digital-only forms. Each barrier can translate into missed screenings, unmanaged long‑term conditions, or late‑stage diagnoses. Place-based policy can change the trajectory: libraries offering advice hubs, colleges running flexible adult courses, and community pharmacies simplifying instructions. The geography of literacy is the geography of survival, and the map can be redrawn with intent.

Practical Levers: From Classrooms to Clinics

If literacy shapes longevity, then the action menu spans education, employment, and every NHS touchpoint. Start early: speech and language support in the early years pays dividends decades later. Continue often: adult learning that respects time, pride, and pay packets. In the health system, the fix is not exotic. It starts with words. Use plain English, short sentences, and familiar terms. Replace jargon with examples. Test materials with patients who have different backgrounds. Make the default easy, not elite.

There are quick wins that cost little and protect lives:

– Redesign appointment letters with clear steps, bold dates, and transport advice.

– Offer teach‑back: clinicians ask patients to explain plans in their own words.

– Send text reminders in simple language; include direct links to reschedule.

– Label medicines with icons and large fonts; avoid ambiguous abbreviations.

– Build digital pathways that work on low‑data connections and basic phones.

– Fund libraries, community centres, and workplaces as learning hubs linked to local NHS teams.

These changes help everyone, not just those with lower literacy. They reduce errors, speed decisions, and free clinical time. Most crucially, they widen the doorway to prevention.

When we treat reading as a health tool, the policy debate sharpens. A nation that invests in literacy invests in longer, healthier lives, with spillovers into productivity and social cohesion. The beauty of this connection is its practicality: schools, libraries, pharmacies, and clinics can act tomorrow. Raising literacy is a public health intervention disguised as education policy. If your council, trust, or workplace chose one change this year—simpler letters, adult classes, a teach‑back pledge—what would you pick, and how would you measure whether the change helped people live not just better, but longer?

Did you like it?4.4/5 (29)