In a nutshell

- 🧠 Stress drives the gut–brain axis via the HPA axis, releasing cortisol and catecholamines that alter gut motility, permeability, and immune signalling, reshaping the microbiome and reducing beneficial SCFAs.

- 🧬 A delicate triangle—hormones, nerves, and microbes—explains symptoms: adrenaline shifts peristalsis, low vagus nerve tone heightens pain, and microbial metabolites feed back to nerves, producing reflux, diarrhoea, or constipation.

- 🚨 Those with IBS or functional dyspepsia show heightened visceral sensitivity; stress amplifies routine meal responses, while erratic eating, high caffeine, alcohol, and poor sleep common in hybrid work patterns worsen bloating and flares.

- 🛠️ Evidence-backed steps: slow diaphragmatic breathing, time-consistent meals, sleep routines, movement, CBT and gut-directed hypnotherapy, reflux tweaks (bedhead elevation, less alcohol/caffeine), and a short-term low FODMAP plan with a dietitian.

- 🔁 The loop is bidirectional: easing stress improves vagal tone and microbial balance; small, consistent changes compound, turning down gut hypersensitivity and stabilising digestion.

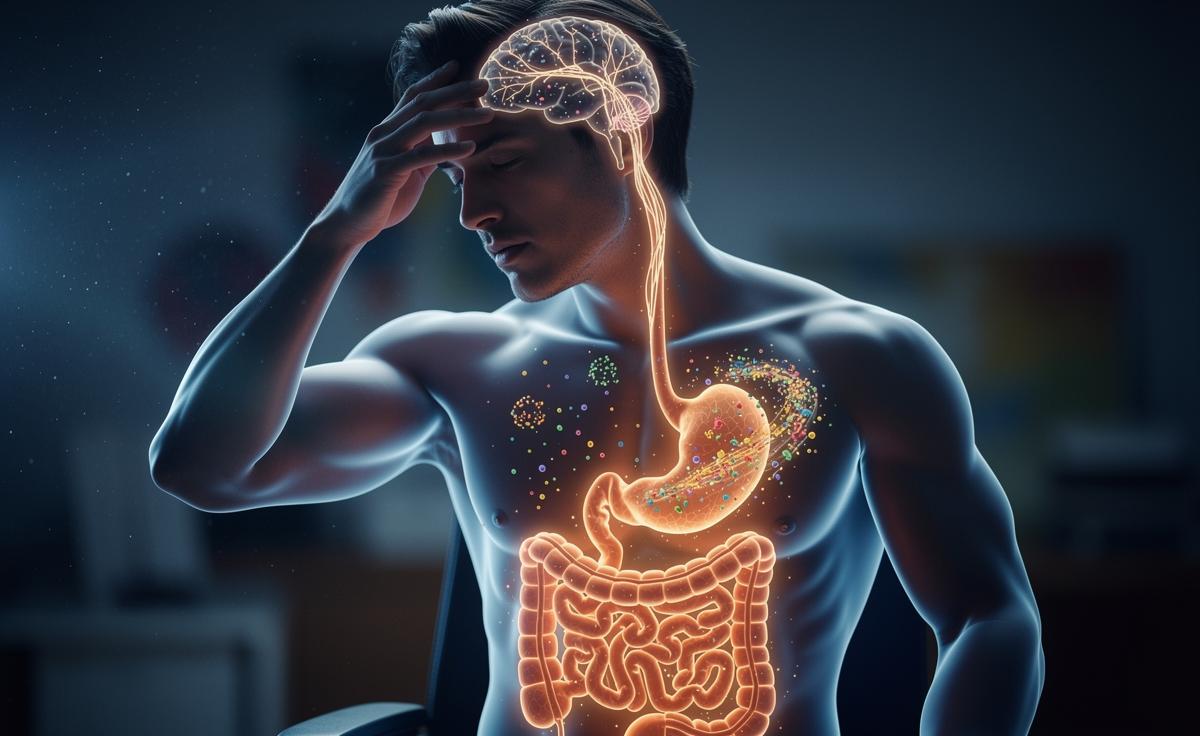

Stress once looked like a problem of the mind alone. Not anymore. A growing stack of studies now shows how pressure at work, sleepless nights, or lingering anxiety can remodel the gut within days, changing what we digest, how we feel, even what we crave. Signals ricochet along the gut–brain axis, altering nerves, hormones, and the trillions of microbes that line our intestines. That’s why an argument can cause cramping. Why deadlines invite acid reflux. When stress sticks around, digestion pays the bill. Understanding the new science helps explain familiar symptoms, but it also points to practical fixes that don’t involve a medicine cabinet.

The Stress–Gut Axis: What Science Now Shows

Researchers describe a two-way highway between the nervous system and the digestive tract. Stress activates the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis, releasing cortisol and adrenaline, which tweak gut motility, tighten or loosen permeability, and blunt the immune system that patrols the intestinal wall. Signals then head back to the brain via the vagus nerve, amplifying vigilance and pain sensitivity. In small doses, that alert state is protective. In chronic doses, it becomes corrosive.

Animal and human data now converge: stress can reduce protective mucus, thin the lining, and shift the balance of gut bacteria away from beneficial, fibre-loving species toward more inflammatory ones. That affects short-chain fatty acids—key fuels for colon cells—and changes the way we metabolise bile acids and carbohydrates. It’s not just butterflies in the stomach; stress reshapes the habitat those butterflies live in. Once the ecology tilts, symptoms often follow: bloating, urgency, constipation, and a disconcerting sense that the gut is always “on”.

Hormones, Nerves, and Microbes: A Delicate Triangle

Think of digestion as choreography. Hormones set tempo, nerves cue the dancers, microbes fill the orchestra pit. Under stress, the tempo skews. Cortisol and catecholamines modulate immune cells in the gut wall, which then change the chemicals they release. Enteric nerves respond, altering peristalsis—the muscle waves that push food along. Microbes sense those shifts and adjust, producing different metabolites that feed back to nerves and immunity. When one corner of the triangle slips, the others follow. The result can be rapid transit and diarrhoea for some, sluggish colons and reflux for others, depending on baseline physiology and diet.

Key players and their likely gut effects appear below. It is a simplification, but it captures how stress chemistry translates into sensations at the dinner table and in the loo.

| Mediator | Short-Term Effect | Chronic Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Cortisol | Reduces inflammation briefly; dampens pain | Increases permeability; alters microbiome diversity |

| Adrenaline/Noradrenaline | Speeds or stalls motility; tightens sphincters | Visceral hypersensitivity; reflux or constipation patterns |

| Vagus nerve tone | Improves stomach emptying when high | Low tone linked with IBS symptoms and anxiety |

| Microbial metabolites | Modulate gut pH; fuel colon cells | Shifted SCFAs; pro-inflammatory signals |

These loops are bidirectional. Improve sleep, ease the HPA axis, and vagal tone rises. Beneficial microbes rebound. Signals quieten. That is why mind–body tools can feel like digestive tools—because biologically, they are.

From Indigestion to IBS: Who Feels It Most

Not everyone reacts the same way. People with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) or functional dyspepsia often have heightened visceral sensitivity, meaning normal pressure or gas feels painful. Stress amplifies that sensitivity, so routine meals provoke outsized responses. Those recovering from a gut infection may be vulnerable too; low-grade inflammation and altered microbes can linger, and stress pushes the system off balance again. In these groups, even small life changes can tip symptoms from background noise to centre stage.

Patterns matter. Rushed breakfasts, long gaps, then heavy late dinners set the scene for heartburn and bloating. High-caffeine days pulse the colon, then rebound. Alcohol loosens the lower oesophageal sphincter and muddles sleep, compounding stress the next day. For many in the UK juggling hybrid work, this erratic rhythm is familiar—and so are the consequences: cramps on the commute, urgent dashes, or constipated weekends. Clinicians now look beyond scans and bloods, asking about workload, sleep, and support networks because these predict symptom flares almost as well as a food diary.

Practical Steps Backed by Evidence

There is no single cure, but several low-risk strategies can steady the triangle. Start with breathing as a lever: five minutes of slow diaphragmatic breathing (about six breaths per minute) can raise vagal tone and reduce gut pain perception. Pair it with time-consistent meals: aim for regular eating windows and avoid very late, heavy dinners. Routine calms physiology. Many benefit from a prebiotic nudge—oats, onions, beans—though during flares a gentle approach (well-cooked veg, smaller portions) is kinder.

Sleep is medicine. Protect a fixed wake time, dim screens an hour before bed, and keep bedrooms cool. Movement helps too. Brisk walks or cycling improve motility and insulin sensitivity, which support a healthier microbiome. Psychological therapies have gut payoffs: gut-directed hypnotherapy and CBT show meaningful symptom reductions in trials. If reflux dominates, trial reducing alcohol and late caffeine, elevating the bedhead, and loosening waistbands. For complex cases, discuss a low FODMAP trial with a registered dietitian; it’s effective short term, but reintroduction is essential to protect microbial diversity.

Stress changes digestion; digestion changes stress. That loop can spiral down or up. The new science does not frame your symptoms as “in your head”—it traces the wiring between head and gut and shows the switches you can reach. Small, consistent choices often beat dramatic overhauls. Track what you change, note how your body answers, and give adjustments a few weeks. Relief is rarely instant, but momentum builds. Which lever will you test first—the breath, the plate, the pillow, or the pace of your day?

Did you like it?4.5/5 (27)