In a nutshell

- 🧠 Procrastination is an emotion-management problem more than a time one, driven by the urge to avoid anxiety, uncertainty, and self-doubt.

- ⌛ Studies highlight present bias and mood repair: we choose short-term relief over long-term goals, especially when tasks feel aversive or unclear.

- 🧩 Gaps in executive function, weak future self-continuity, and the intention–action gap explain why plans fail at the moment of action.

- 🚩 Key triggers include low expectancy, low value, high cost, long delay, plus ambiguity, perfectionism, and the planning fallacy.

- 🛠️ Effective tactics: implementation intentions, time boxing, Pomodoro, environmental design, self-compassion, pre‑commitment, value reframing, and task granularity.

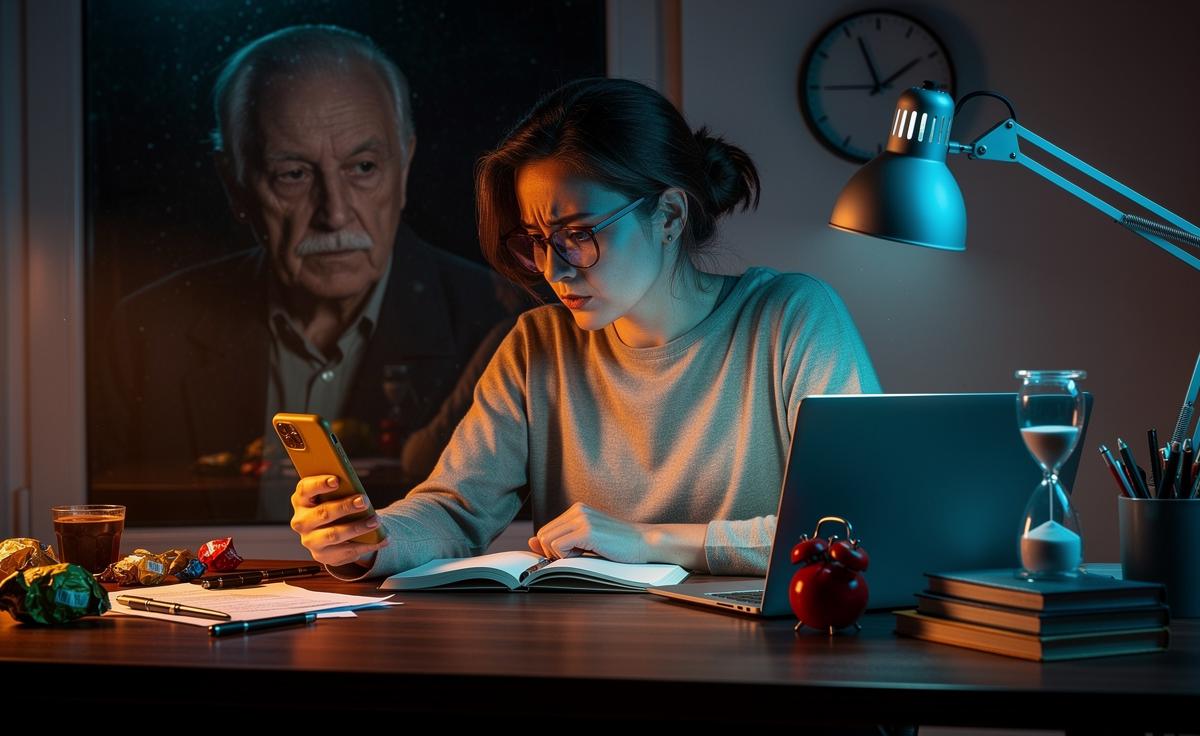

We blame laziness, bad calendars, even the weather. Yet the truth of procrastination is subtler, and far more human. Psychological research shows that delay is rarely about clocks; it’s about feelings, expectations, and the brain’s tug‑of‑war between long-term goals and immediate comfort. In a deadline culture that prizes busyness, we quietly seek relief from anxiety, uncertainty, and self-doubt, and call it “checking email.” Procrastination is not a time-management problem; it is an emotion-management problem. What follows is a guided look at what the best studies reveal—why we defer, when we’re most vulnerable, and how small, evidence-based shifts can reduce the drag without draining your ambition.

The Psychology Behind Delay: Present Bias and Mood Repair

At the heart of procrastination sits present bias: we overweight immediate outcomes and underweight future consequences. A task that promises distant rewards but guarantees discomfort today loses the internal vote. Neuroscience suggests this bias is amplified by limbic reward circuits that favour short-term relief, leaving the reflective prefrontal systems outgunned when stress rises. The result looks like poor discipline. It often isn’t. It’s a predictable valuation glitch.

Classic experimental work by researchers including Roy Baumeister and Dianne Tice found that students under stress delayed difficult tasks because those tasks worsened their mood. Postponement, even for minutes, improved how they felt—briefly. Later studies by Tim Pychyl and Fuschia Sirois sharpened the point: short-term mood repair drives long-term delay. Avoiding a report, a hard conversation, or a gym session functions as a quick anaesthetic. The bill arrives later with interest: more anxiety, tighter time, lower quality.

Crucially, the effect intensifies with task aversiveness (boring, complex, or ambiguous work) and with people high in trait negative affect. This is why advice like “just start” works when tasks are clear and stakes are low, and collapses when ambiguity or fear dominate. When the brain expects pain, it bargains for escape.

Executive Function, Identity, and the Intention–Action Gap

Another strand of research points to the machinery of executive function—working memory, inhibition, and planning. When these systems are overtaxed by stress, distraction, or sleep loss, follow-through suffers. People with ADHD, whose executive networks are differently tuned, report higher chronic procrastination not because they don’t care, but because sustaining effort on non-rewarding tasks is harder. The environment can worsen it: notifications, clutter, and multitasking siphon the mental bandwidth needed to hold a plan steady.

Identity matters too. Studies on future self-continuity show we treat our future selves like semi-strangers. If “tomorrow-you” feels distant, you’re likelier to offload pain onto them. Self-discrepancy research adds that harsh self-criticism inflames avoidance: the more you fear being exposed as inadequate, the more you dodge the proving ground. A fragile sense of competence is gasoline on the procrastination fire.

Enter the famous intention–action gap. We mean to do it. We even schedule it. Then the moment arrives and the brain whispers, “Not yet.” Implementation intentions—if‑then plans such as “If it’s 9 a.m., I open the report and write 50 words”—reduce the gap by delegating control to cues rather than moods. The science is plain: specifics beat slogans, and friction beats willpower when attention is scarce.

Situations That Trigger Procrastination, According to Research

Not all tasks tempt delay equally. Studies consistently identify four triggers: low expectancy of success (I’ll fail), low value (Why bother?), high cost (This will hurt), and high delay (Pay-off is far away). Uncertainty—about instructions, criteria, or outcomes—magnifies all four. Perfectionism, often praised in hiring brochures, can be corrosive in practice; when the “acceptable” bar is imagined as impossibly high, starting feels unsafe. Then there’s the planning fallacy: we underestimate time, overestimate focus, and leave too little slack. Delay becomes almost rational.

Common triggers and evidence-backed cues are summarised below.

| Trigger | Representative Finding | Useful Cue |

|---|---|---|

| Low expectancy | People delay when success feels unlikely | Start with a tiny win to raise perceived competence |

| Task aversiveness | Unpleasant tasks spur mood repair | Pair with a reward; temptation bundling |

| Ambiguity | Unclear steps increase avoidance | Write the first actionable step in one sentence |

| Long delays | Distant outcomes lose motivational power | Create short deadlines and visible progress markers |

Ambiguity is rocket fuel for postponement. Clarify the next action, shrink the task until it fits the current hour, and the emotional temperature drops. In lab terms, you’re changing the payoff matrix; in lived terms, you’re making motion feel safe.

What Actually Helps: Evidence-Based Strategies

Evidence favours gentle systems over heroic sprints. Implementation intentions turn intentions into scripts: “If it’s after lunch, I draft the email template.” Time boxing caps exposure: fifteen minutes on the messy draft, timer set. The Pomodoro Technique adds enforced breaks that keep aversion from spiking. Environmental tweaks—blocking distracting sites, laying out tools the night before, keeping only one window open—reduce the need for veto power in the moment.

Self-compassion is not a platitude; studies link it to lower procrastination because it softens the shame–avoidance loop. When mistakes are survivable, starting becomes possible. In practice, that means reviewing a miss without self-attack, extracting one lesson, and scheduling a retry. Pre‑commitment devices help too: public deadlines, peer check-ins, or deposit contracts that cost you money if you skip.

Two more levers matter. First, value reframing: connect the task to identity (“I’m the colleague who delivers clean drafts”), not just outcomes. Second, granularity: break tasks into steps that can be finished in a sitting, each with a visible endpoint. The research through-line is clear: change the context, simplify the next action, and let structure carry the load your mood cannot.

Procrastination thrives where emotions run hot, outcomes feel distant, and paths look foggy. Science doesn’t damn us for it; it offers tools to cool the heat and shorten the path. Small cues and kinder self-talk can outmuscle willpower alone, because they reshape the choice architecture that triggers delay. You are not your worst afternoon. If you picked one task today and made it safer, smaller, and sooner, what would shift—and which future version of you might finally get a fair chance?

Did you like it?4.6/5 (25)